-2.jpg)

There was one visit that, no matter what, I was going to accomplish whilst in Saigon: the War Museum.

I was, if one can say such a thing, looking forward to it. Not excitement, not anticipation—just an all-round feeling of something I’ve got to see. When I left, I was in shock—disgusted, horrified, disturbed—but still very glad I went.

What did I know about the Vietnam War? Yes, you guessed it: from movies and the odd documentary here and there, which obviously came with the caveat of being, almost to a point, very American-centric, if not totally Western-centric. Granted, this is not the greatest way to go into something like this, but I think those in charge know this about a vast number of visitors.

Sure, there have been some very anti-war movies—Rambo, Platoon, and Full Metal Jacket, to name just three—but they are still (mostly) told from one side only. This was my first foray into the stories told by those on the other side—the ones who were invaded.

For an entry fee which amounted to essentially nothing, you are simply let loose to explore as you see fit, although you can pay for a personal guide if you wish, available in a number of languages. I opted for the former and was immediately greeted by planes, choppers, tanks, artillery—oh, and bombs. Lots and lots of bombs, both unexploded and in huge pieces of shrapnel.

(11).jpg)

So far, so very “war museum.” Nothing out of the ordinary, despite most of it being American (most equipment was quickly left behind), all outside, and with no problem if you touch them. Then you go inside the three-storey building.

They knew exactly what they were doing when it came to the layout: boys’ toys, then general photography, artwork, declarations of peace, and then...

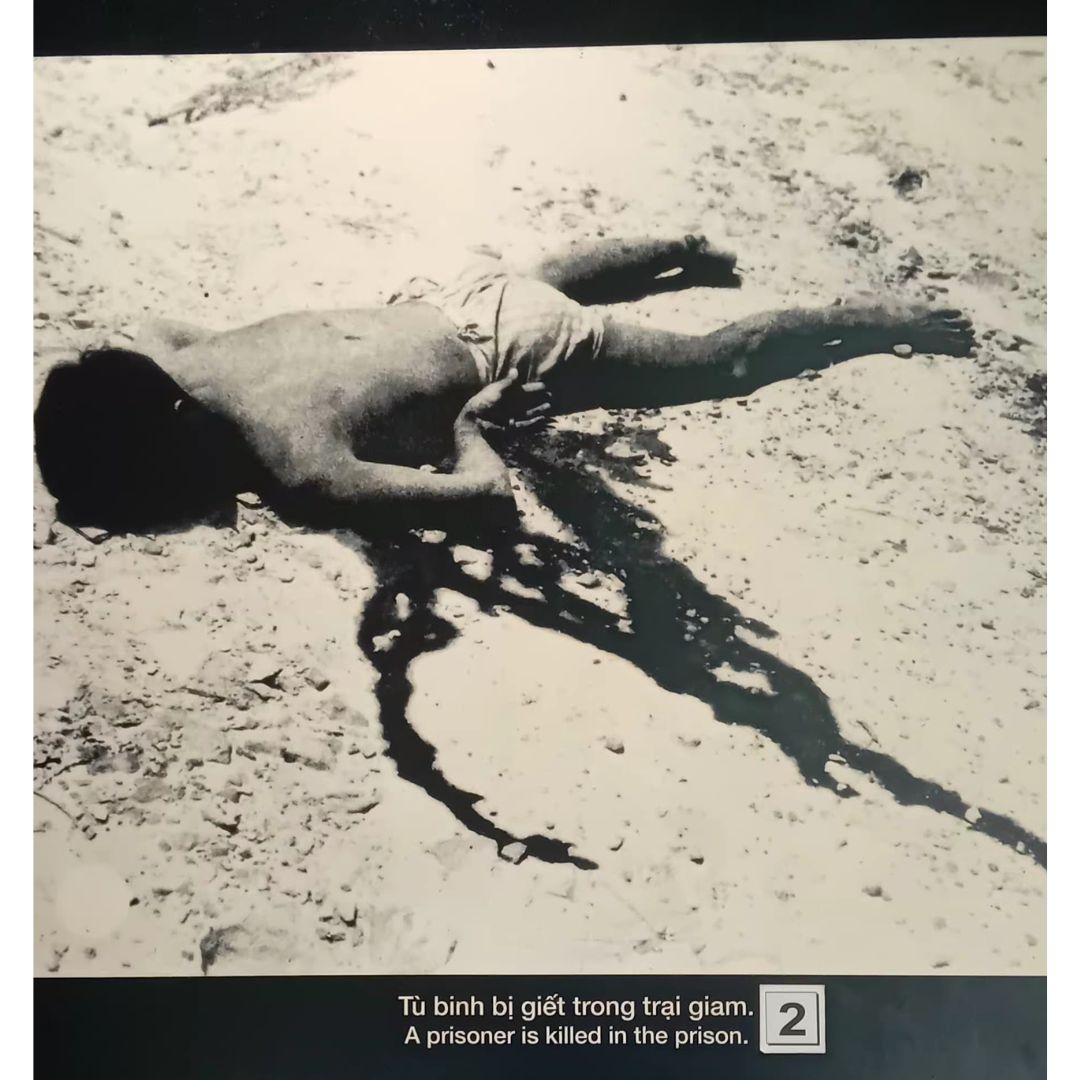

Before I continue, I will point out that this museum does not hold back; it is raw. It was fairly busy when I arrived a little after midday, and I noticed many children amongst the throngs, including what I could only presume was a school group. Maybe the government insists it’s part of the curriculum. It probably should be.

Horror movies—the truly great ones like The Exorcist or The Shining—slowly drag you in. You are aware of what you’re seeing, what you’re a part of, and then they leap out of the shadows and hit you hard. This is the best analogy I could come up with to describe what followed.

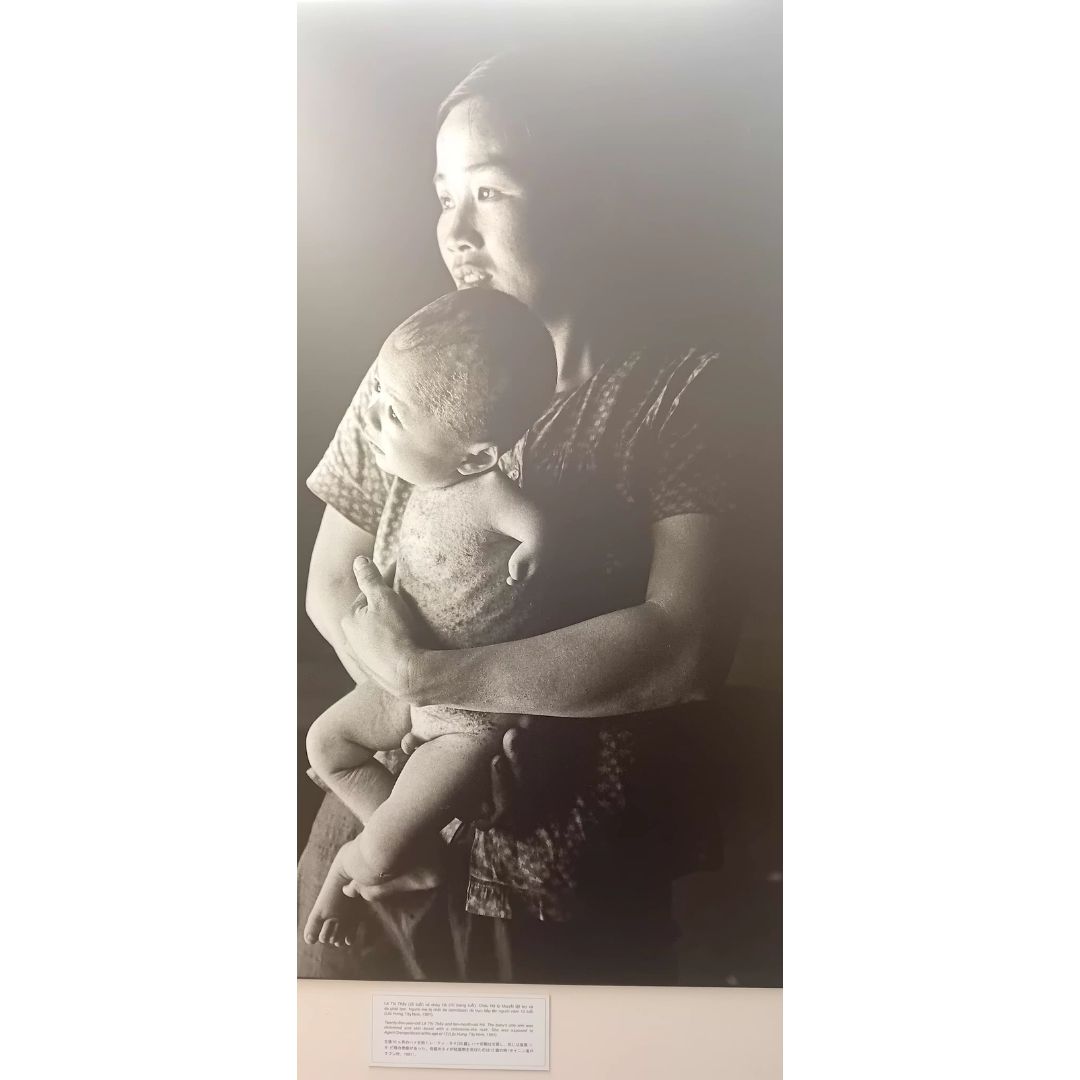

Deformed children because of Agent Orange. Vietnamese villagers with limbs blown off. Pregnant women murdered. Bodies barely recognisable as human. Babies shot through the head. Actual foetuses. Inhumane torture equipment and physical evidence of what the Americans did. Entire villages of people on fire, piled in heaps. Stories of rape. Burns so severe that bones jutted out where arms should have been.

I could go on and on—and as I took picture after picture, I wondered how many of these atrocities we’d be able to publish. I suspect not all.

You watch movies and they can move you—particularly when based on fact—but to stand face to face with a child with half its face blown off, an actual thing that happened to a real child, and now you are seeing it for the first time in person... I am not suggesting that all war crimes were committed by the Americans, because they definitely were not—this is warfare, and black and white very quickly go out of the window—but all I am saying is that babies are not the enemy.

I refuse to get into why it all happened, because that would drag us back to Kennedy, probably to the Korean War, and Stalin. But I think it’s safe to say that, no matter how you feel, no matter where you stand, no matter your political affiliation, this war—this period of immeasurable loss of life on both sides—should never have happened.

The Vietnamese people were forced into a war they neither asked for nor wanted, against, at the time, an enemy who was infinitely superior. They dug in, fought, and paid for it with their lives. And yet they still came through.

Many Americans who held power at the time—many in the military and from both sides of the political spectrum—went on record to say it should never have happened. But there are some who still believe it was the right thing to do. I’m sure, in Vietnam, there are some who hold deep resentment and anger—and who can blame them?

.jpg)

But to both I ask: why?

I met two vets whilst here. Both showed me their injuries during limited conversation, although admittedly the second could not hide his—for he had had both his arms blown off. He offered a handshake of sorts, so I obliged and shook his stump.

But, over in the US, there are also so many who returned with life-changing injuries and PTSD. They had to just deal with it, and many were abandoned by the very system that sent them there in the first place.

Let’s be clear here: nobody won this. Everybody suffered.

I say nobody won—because in war nobody ever does—but Vietnam definitely did not lose. And as much as a few of those hard and steadfast Americans may puff out their chests and salute the flag, America lost it. And they lost twice because of their treatment of the US vets when they returned. This was American politics at its absolute worst.

I implore you to go and see this. I beg you to find out what really happened. It will be uncomfortable; it will shock you to your core—as it did with the many Americans I met visiting this museum. I agree it’s a long way to come for just that—and it is—but come and soak up what Vietnam has to offer. It’s a truly beautiful country, and its people are treasured. Just don’t ignore the War Museum.

_(26).jpg)

-2.jpg)

-3.jpg)

-3.jpg)

-3.jpg)

-3.jpg)

-2.jpg)

-2.jpg)

-3.jpg)

-3.jpg)