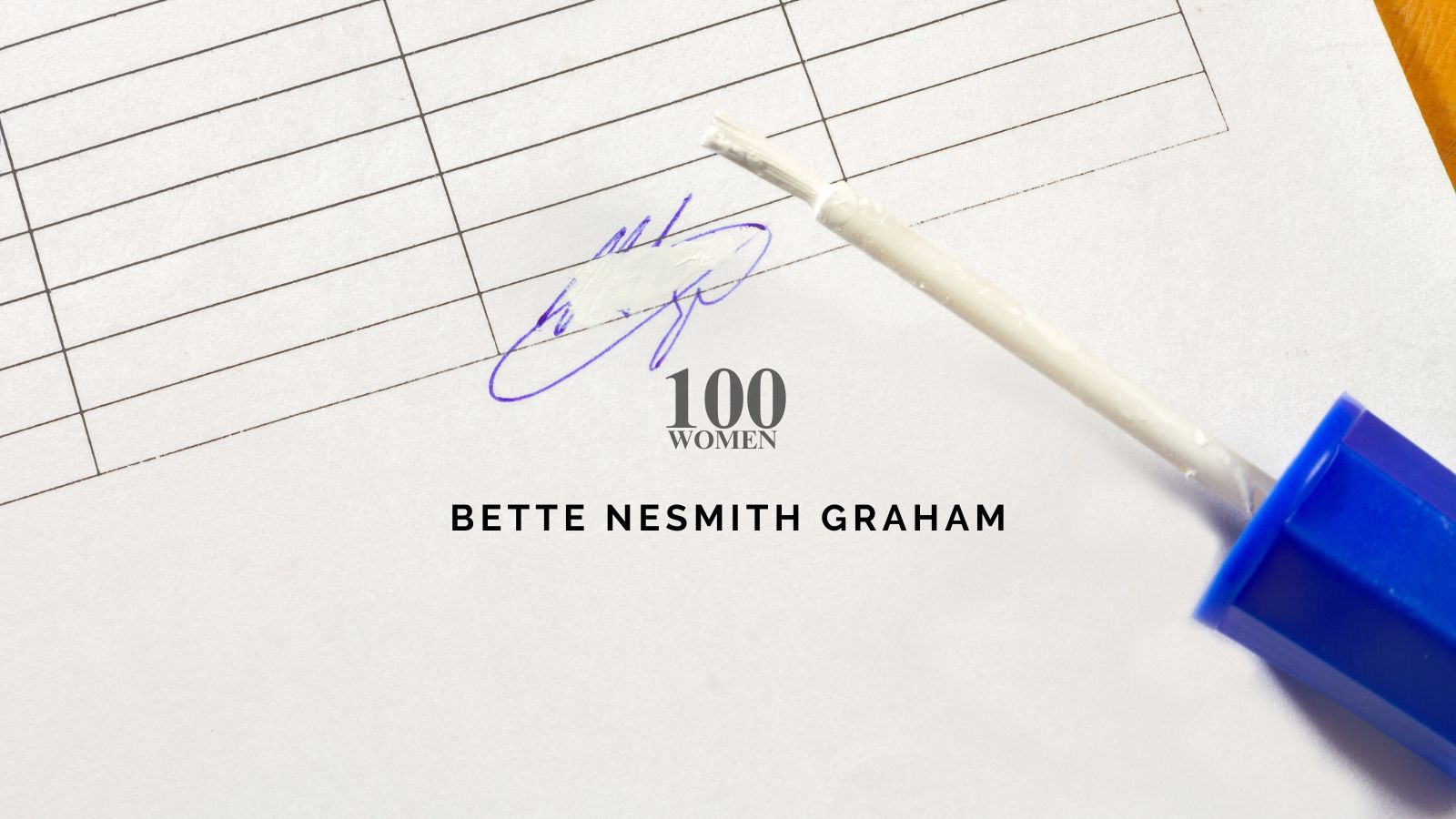

In the early 1950s, long before computers or autocorrect, one small typing mistake could ruin an entire page of work. For secretaries, retyping documents was part of the daily grind. Among them was Bette Nesmith Graham, a single mother in Texas, working as an executive secretary at a bank.

Like many women in her role, she typed fast and often. But she was also a painter, and one day she realised that artists don’t erase mistakes—they cover them. That thought would become the seed of a quiet revolution.

After hours at her kitchen table, Graham mixed up her first batch of “Mistake Out” using white tempera paint. She poured it into small bottles and carried it to the office, applying it with a tiny brush whenever she made an error. At first, it was just her secret trick to make the workday smoother.

But soon, colleagues noticed. They wanted a bottle too. Graham began making extras, bottling them in old nail polish containers, and handing them out to other secretaries. Word spread quickly through offices in Dallas.

By 1956, demand had grown so much that Graham officially started selling the product from her home. She named her little company the Mistake Out Company. Marketing in those early days wasn’t through billboards or television—it was through word of mouth. Secretaries talked. Offices buzzed with the discovery.

She didn’t have much in the way of advertising budget, but she had networks of working women, and she understood their struggles. Graham’s product wasn’t just a convenience—it saved hours of time, reduced stress, and helped secretaries present perfect pages. That practical usefulness did all the selling she needed in the beginning.

Graham’s journey wasn’t without challenges. She tried pitching her invention to large companies, including IBM, but was rejected. For years she balanced her full-time job, raising her son Michael, and building her side business at night.

She stuck with it. With help from her son and friends, she filled orders, packed boxes, and sent them out to offices across the country. The small operation began to grow into something bigger.

In 1968, she renamed her product Liquid Paper, giving it a stronger, more professional identity. Sales increased steadily. By the mid-1970s, she had opened her own headquarters and built a manufacturing plant. The little bottles that began in her kitchen were now being produced by the millions.

In 1979, after more than two decades of persistence, Bette Nesmith Graham sold Liquid Paper to Gillette for $47.5 million.

Graham wasn’t just an inventor; she was also a philanthropist. After the sale, she dedicated much of her wealth to supporting women in the arts and education.

Her invention may have started as a way to fix small mistakes, but it became something larger: a symbol of how ordinary challenges can inspire extraordinary ideas.

Bette Nesmith Graham’s story reminds us that innovation doesn’t always start in laboratories or boardrooms. Sometimes, it begins in a kitchen with a single mother, a paintbrush, and a bit of persistence.

She turned a simple frustration into a tool that changed office work around the world. Her legacy lives on every time someone finds a creative solution to a problem others might overlook.